I've always been a huge fan of Down East Magazine, widely considered the best magazine about life in Maine. No matter how bookish you may be, no matter how learned in the written word, it's the stunning photography that draws you into the magazine. Only after you find a comfortable spot to delve into the articles do you come to appreciate the quality of the writing. That's what brings you back month after month.

In June of this year, I took a couple chapters from my as yet unpublished memoir, blended them into a single essay, and chopped it down to meet their word limit. I submitted the essay in late June, then I pretty much forgot about it.

Two months later I heard back. They wanted to publish the piece in their November edition. Given that I had written about deer hunting with my father, the timing was perfect. They even paid me a modest sum. They didn't know (or maybe they did) that I would have paid them to print my essay. After all, their monthly circulation is about 100,000 copies.

We went through a couple rounds of editing, and the finished product is now on newsstands—Down East Magazine, November 2016 edition, page 48. The essay is entitled "Deer Spotting: A longtime sportsman faces down illness — and heads out into the field one last time."

What a thrill this has been for me.

Now, back to work on finding a literary agent for my book…

Note: As of now there is no free, public link to the story, but I'll let you know if that changes. For anyone who is interested in purchasing the November issue of Down East for $5.99, click here. To purchase a subscription, click here.

Tuesday, October 25, 2016

Tuesday, October 18, 2016

As Hope Fades, I Press on: Here’s How

Hope can be an effective

tool to ease human suffering. In many cases, though, it’s not enough.

After my diagnosis 15 years ago, I set out to become the most informed patient on the planet. Even though there were no FDA-approved treatments for primary progressive multiple sclerosis (and there still aren’t), I knew the answer was out there. I just needed to be smart, brave, and hard-working enough to find it. Oh, and cocky too. Every fighter needs a little swagger.

I tried chemotherapy and immunosuppressants. No luck. I self-administered daily, painful shots. Didn’t help. I participated in a clinical trial where I had to drive two hours each way, two times a month, for two years. It slowed down progression for a while; then it didn’t. I convinced interventional radiologists to thread catheters from my groin into one side of my heart and out the other, so that they could balloon supposed restrictions in my internal jugular veins—twice. In retrospect, I doubt there was anything wrong with those veins. I lobbied doctors to inject powerful medicine into my spinal cord every two months for two years. Again, helped for a while; then it didn’t. I pursued all these treatments in the hope that I might slow down, stop, or even reverse the course of my disease. Instead, I progressed from a limp to a cane to a wheelchair, and my arms and hands are headed in the same direction.

Understandably, I began to lose hope that I would ever find a medical solution. I discussed this with a well-intentioned friend who warned me, “If you don’t have hope, you have nothing, right?”

No. That didn’t describe how I felt. As hope faded, something else took over, and it wasn’t despair. I remained in generally good spirits, even though I knew I might never get better. Something more impassive, almost comforting had intervened.

Acceptance.

Where hope receded, acceptance filled the void.

It’s not that I studied the alternatives and chose acceptance as the best path forward. It lived inside me the whole time, waiting to be called upon. Perhaps I inherited it from my mother or learned it by watching her live as a quadriplegic for 39 years. No matter its origin, I was fortunate to have such a tool at my disposal. I suspect, however, that acceptance can be discovered, learned, or acquired if you don’t possess it already.

Acceptance should not be confused with surrender, although the differences are subtle. Surrender carries a negative connotation. “I give up. Do with me what you will.” Acceptance carries a neutral connotation, “If this is my life, then so be it,” or sometimes a positive connotation, “If this is my life, I will make the best of it.” In its purest form, acceptance has a Zen feel to it. You are exactly where you are supposed to be in life. Don’t fight it. Embrace it.

I don’t lament what might have been, envy what healthy people can do, or ask “why me?” I’m grateful for what I have, and I accept what I’ll never again be.

I haven’t given up all hope. I continue to keep one ear to the MS research world. In a dispassionate manner, I evaluate each potential treatment on its merits. But I don’t rely on this hope to motivate me. I’m not emotionally invested in it. I keep hope around only for practical reasons, so that I don’t miss an opportunity for a treatment that may work. There is a lot of research going on. I just don’t know if it will become available to me in time.

Hope is the much sexier cousin to Acceptance. Hope can produce spectacular results. Books and songs have been written about the power of Hope. Acceptance does its work anonymously. The results, important though they may be, don’t garner much attention, save for this obscure essay. Although it may seem counterintuitive, I find that hope and acceptance work together quite well.

For my healthy and disabled readers: how do you manage hope and acceptance in your lives?

After my diagnosis 15 years ago, I set out to become the most informed patient on the planet. Even though there were no FDA-approved treatments for primary progressive multiple sclerosis (and there still aren’t), I knew the answer was out there. I just needed to be smart, brave, and hard-working enough to find it. Oh, and cocky too. Every fighter needs a little swagger.

I tried chemotherapy and immunosuppressants. No luck. I self-administered daily, painful shots. Didn’t help. I participated in a clinical trial where I had to drive two hours each way, two times a month, for two years. It slowed down progression for a while; then it didn’t. I convinced interventional radiologists to thread catheters from my groin into one side of my heart and out the other, so that they could balloon supposed restrictions in my internal jugular veins—twice. In retrospect, I doubt there was anything wrong with those veins. I lobbied doctors to inject powerful medicine into my spinal cord every two months for two years. Again, helped for a while; then it didn’t. I pursued all these treatments in the hope that I might slow down, stop, or even reverse the course of my disease. Instead, I progressed from a limp to a cane to a wheelchair, and my arms and hands are headed in the same direction.

Understandably, I began to lose hope that I would ever find a medical solution. I discussed this with a well-intentioned friend who warned me, “If you don’t have hope, you have nothing, right?”

No. That didn’t describe how I felt. As hope faded, something else took over, and it wasn’t despair. I remained in generally good spirits, even though I knew I might never get better. Something more impassive, almost comforting had intervened.

Acceptance.

Where hope receded, acceptance filled the void.

It’s not that I studied the alternatives and chose acceptance as the best path forward. It lived inside me the whole time, waiting to be called upon. Perhaps I inherited it from my mother or learned it by watching her live as a quadriplegic for 39 years. No matter its origin, I was fortunate to have such a tool at my disposal. I suspect, however, that acceptance can be discovered, learned, or acquired if you don’t possess it already.

Acceptance should not be confused with surrender, although the differences are subtle. Surrender carries a negative connotation. “I give up. Do with me what you will.” Acceptance carries a neutral connotation, “If this is my life, then so be it,” or sometimes a positive connotation, “If this is my life, I will make the best of it.” In its purest form, acceptance has a Zen feel to it. You are exactly where you are supposed to be in life. Don’t fight it. Embrace it.

I don’t lament what might have been, envy what healthy people can do, or ask “why me?” I’m grateful for what I have, and I accept what I’ll never again be.

I haven’t given up all hope. I continue to keep one ear to the MS research world. In a dispassionate manner, I evaluate each potential treatment on its merits. But I don’t rely on this hope to motivate me. I’m not emotionally invested in it. I keep hope around only for practical reasons, so that I don’t miss an opportunity for a treatment that may work. There is a lot of research going on. I just don’t know if it will become available to me in time.

Hope is the much sexier cousin to Acceptance. Hope can produce spectacular results. Books and songs have been written about the power of Hope. Acceptance does its work anonymously. The results, important though they may be, don’t garner much attention, save for this obscure essay. Although it may seem counterintuitive, I find that hope and acceptance work together quite well.

For my healthy and disabled readers: how do you manage hope and acceptance in your lives?

Wednesday, October 12, 2016

My Daughter’s Wedding

Three dates I'll always remember:

On October 22, 2001, I was diagnosed with MS.

On July 11, 2008, I started using a wheelchair.

On August 20, 2016, I walked my daughter down the aisle.

People from all over the country descended on Hardy Farm in Fryeburg, Maine, that weekend. Dave and Stephanie King, who got married in our backyard last summer (click here), flew in from Las Vegas. More on Dave later. Kim’s brother and his family drove from Michigan. No less than five of our friends pried themselves away from Cleveland, where the celebration of the Cavaliers' NBA championship was (and is) still going strong, to visit the woods of western Maine. Folks from every corner of New England also made the drive.

On October 22, 2001, I was diagnosed with MS.

On July 11, 2008, I started using a wheelchair.

On August 20, 2016, I walked my daughter down the aisle.

People from all over the country descended on Hardy Farm in Fryeburg, Maine, that weekend. Dave and Stephanie King, who got married in our backyard last summer (click here), flew in from Las Vegas. More on Dave later. Kim’s brother and his family drove from Michigan. No less than five of our friends pried themselves away from Cleveland, where the celebration of the Cavaliers' NBA championship was (and is) still going strong, to visit the woods of western Maine. Folks from every corner of New England also made the drive.

Just like last summer, my brother

Tom officiated the ceremony. One of the difficult decisions Amy and I had to make was

whether I would attempt to walk her down the aisle. Given the rustic

setting of our venue, we would be navigating up a grassy hill, over a

footbridge, around a stump, and through the dirt to get her where she needed

to be. For the past couple of years, I’ve been crossing my fingers that my iBOT

wheelchair would still be operational on August 20, 2016, and it was. Still, we

worried that Amy’s wedding dress train would get caught up under my wheels. I really

wanted to walk her down the aisle. It’s something every father dreams of. Imagine, if you will, how it might feel for someone in a wheelchair.

Amy had put me in charge of writing the ceremony. Leading up to the rehearsal on Friday afternoon, she and I were still tweaking the script, and we needed to make a decision. A crowd of people had gathered in the kitchen where I had my computer set up, so I pulled Amy aside.

“I would love to walk you down the aisle tomorrow, but …”

Amy had put me in charge of writing the ceremony. Leading up to the rehearsal on Friday afternoon, she and I were still tweaking the script, and we needed to make a decision. A crowd of people had gathered in the kitchen where I had my computer set up, so I pulled Amy aside.

“I would love to walk you down the aisle tomorrow, but …”

“Absolutely. Let’s do it. I’m only

going to wear my wedding dress once. I really

don’t care if it gets run over.”

I burst into tears of joy and buried my head in Amy’s shoulder. Just kidding. I was thrilled, though. I may have cracked a smile.

Everything proceeded wonderfully for the rest of the weekend. After the ceremony, Kim said Amy's train came so close to my wheels that she couldn’t understand how I didn’t run over it. Amy and I had kept our gaze on the altar, so we oblivious. Had such a calamity occurred, we would have laughed it off anyway.

Back to Dave King. On July 5, 1986, about 30 years ago, he sang a song at our wedding reception—Landslide by Fleetwood Mac. Amy appreciates history and tradition, so she asked Dave to sing the same song at her wedding. Here’s a video showing a little from both of those performances. Remember, the video of 1986 is from a 30-year-old VCR tape recently digitized, and the 2016 song was shot by Stephanie using a smart phone from about 30 feet away. However, the message of friendship spanning decades and generations couldn't be more clear.

I burst into tears of joy and buried my head in Amy’s shoulder. Just kidding. I was thrilled, though. I may have cracked a smile.

Everything proceeded wonderfully for the rest of the weekend. After the ceremony, Kim said Amy's train came so close to my wheels that she couldn’t understand how I didn’t run over it. Amy and I had kept our gaze on the altar, so we oblivious. Had such a calamity occurred, we would have laughed it off anyway.

Back to Dave King. On July 5, 1986, about 30 years ago, he sang a song at our wedding reception—Landslide by Fleetwood Mac. Amy appreciates history and tradition, so she asked Dave to sing the same song at her wedding. Here’s a video showing a little from both of those performances. Remember, the video of 1986 is from a 30-year-old VCR tape recently digitized, and the 2016 song was shot by Stephanie using a smart phone from about 30 feet away. However, the message of friendship spanning decades and generations couldn't be more clear.

For those of you receiving

this through email, please click here to watch the video.

And here are a few more photos from Amy’s wedding. Click on individual pictures to enlarge them.

And here are a few more photos from Amy’s wedding. Click on individual pictures to enlarge them.

Kim and I being introduced…

Kim's father quite ably stepped in for me

on the father/daughter dance…

Tuesday, October 4, 2016

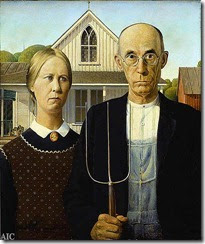

The Parable of the Farmer and His Four Sons

Once upon a time, in a faraway land called Happy Valley, there lived a good and honest sharecropper, his wife, and his four capable sons, who were actually two sets of twins. One set of twins, sturdy and strong, could stand up to anything. These brothers were so in sync with one another that many considered them to be joined at the hip. The other twins, less strong but more agile, were best suited for complex farm chores. They worked hand-in-hand to assist the Farmer.

One year, at harvest time, one of the sturdy and strong sons grew tired and listless. At harvest time the next year, his twin began to feel the same way. They continued to get weaker until after a number of years they became lame and could not help out with the farm work at all. Luckily, the other set of twins remained healthy and used their agility to keep the farm going.

But this didn't last. Eventually, one of the agile twins began to feel weak, just like the sturdy twins had years earlier. And, sure enough, after one more season, the other agile twin followed suit. Everybody slowly got worse over time. Today, the formerly sturdy and strong twins, who could stand up to anything, can't move at all and must be carried everywhere. One of the agile twins is in the same boat. The other agile twin is hanging on, but getting more lame every day.

Today, the Farmer relies on the semi-lame, agile twin and the goodwill of the farmer’s (lovely) wife to fertilize the soil, plant the seeds, and harvest the crops…of life.

To be continued.

One year, at harvest time, one of the sturdy and strong sons grew tired and listless. At harvest time the next year, his twin began to feel the same way. They continued to get weaker until after a number of years they became lame and could not help out with the farm work at all. Luckily, the other set of twins remained healthy and used their agility to keep the farm going.

But this didn't last. Eventually, one of the agile twins began to feel weak, just like the sturdy twins had years earlier. And, sure enough, after one more season, the other agile twin followed suit. Everybody slowly got worse over time. Today, the formerly sturdy and strong twins, who could stand up to anything, can't move at all and must be carried everywhere. One of the agile twins is in the same boat. The other agile twin is hanging on, but getting more lame every day.

Today, the Farmer relies on the semi-lame, agile twin and the goodwill of the farmer’s (lovely) wife to fertilize the soil, plant the seeds, and harvest the crops…of life.

To be continued.

Cast of characters:

The sturdy twins – my left leg and my right leg

The agile twins – my left hand and my right hand

The Farmer – me

The moral of the story:

When things start to fall apart, you better make the most out of your remaining assets, and you better have a steadfast support system. “Buying the Farm” is to be avoided until all other avenues have been thoroughly exhausted.(If you remember this story from its initial run in 2011, thanks for sticking around so long.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)